Dance like no one's watching

June is African American Music Appreciation Month, and what better way to celebrate than with some Aretha? Go ahead and shake that thang: Aretha Franklin

****************************************************************************************************

And now:

At this time, you are responsible for the understanding and identifying the following:

1. composition: rule of thirds, phi grid and Fibonacci spiral

2. how a photographer employs lines, patterns, textures, depth of field (choice as to what is in focus) and symmetry as a communication tool within a photograph.

3. how camera angles convey dialogue and the relationship that the photographer wishes to communicate with the view

4. identify the horizon line

5. techniques to photograph landscapes, buildings and people / animals.

Now we are going to look at lighting. Below you will find general tips on lighting with examples. Take your time and review the following material on light. You are responsible for understanding the impact of the origin (position) and width (broad as opposed to narrow) source of the light and its impact on a subject.

1. composition: rule of thirds, phi grid and Fibonacci spiral

2. how a photographer employs lines, patterns, textures, depth of field (choice as to what is in focus) and symmetry as a communication tool within a photograph.

3. how camera angles convey dialogue and the relationship that the photographer wishes to communicate with the view

4. identify the horizon line

5. techniques to photograph landscapes, buildings and people / animals.

Now we are going to look at lighting. Below you will find general tips on lighting with examples. Take your time and review the following material on light. You are responsible for understanding the impact of the origin (position) and width (broad as opposed to narrow) source of the light and its impact on a subject.

Assignment:

1) Watch the two short videos on types of photography

2) Please respond to the following questions based upon the reading.

3) After the reading, there are ten images. Select five and explain where the lighting comes from and how it impacts the photo.

Share by Friday midnight or Sunday midnight, if you receive extra time. Thank you. Questions? Concerns? Please, let's talk. Questions:

1. What happens when light rays hit from several directions?

2. Why does the sun cast such a hard light, despite being over 93 million miles away?

3. How do clouds impact the diffusion of light?

4. So you want to make the those earring sparkle at the prom. What do you do?

5. What happens when you move your light source twice as far from your subject?

6. Why might you prefer side lighting when photographing a landscape?

7. What is a back lit portrait, and where is its light source?

8. What makes a picture have a 3-D look?

1. The broader the light source, the softer the light.

A broad light source lessens shadows, reduces contrast, suppresses texture.

This is because, with a broad source, light rays hit your subject from more directions, which tends to fill in shadows and give more even illumination to the scene.

1. What happens when light rays hit from several directions?

2. Why does the sun cast such a hard light, despite being over 93 million miles away?

3. How do clouds impact the diffusion of light?

4. So you want to make the those earring sparkle at the prom. What do you do?

5. What happens when you move your light source twice as far from your subject?

6. Why might you prefer side lighting when photographing a landscape?

7. What is a back lit portrait, and where is its light source?

8. What makes a picture have a 3-D look?

1. The broader the light source, the softer the light.

A broad light source lessens shadows, reduces contrast, suppresses texture.

This is because, with a broad source, light rays hit your subject from more directions, which tends to fill in shadows and give more even illumination to the scene.

Tip: When photographing people indoors by available light, move lamps closer to them or vice versa for more flattering light.

2. The closer the light source, the softer the light.

The farther the source, the harder the light. This stands to reason: Move a light closer, and you make it bigger—that is, broader—in relation to your subject. Move it farther away, and you make it relatively smaller, and therefore more narrow.

Think about the sun, which is something like 109 times the diameter of the earth—pretty broad! But, at 93 million miles away, it takes up a very small portion of the sky and hence casts very hard light when falling directly on a subject.

Tip: Materials such as translucent plastic or white fabric can be used to diffuse a harsh light source. You can place a diffuser in front of an artificial light, such as a strobe. Or, if you're in bright sun, use a light tent or white scrim to soften the light falling on your subject.

3. Diffusion scatters light, essentially making the light source broader and therefore softer.

When clouds drift in front of the sun, shadows get less distinct. Add fog, and the shadows disappear. Clouds, overcast skies, and fog act as diffusion—something that scatters the light in many directions. On overcast or foggy days, the entire sky, in effect, becomes a single very broad light source—nature’s softbox.

Bouncing light acts as diffusion

Tip: Crumple a big piece of aluminum foil, spread in out again, and wrap it around a piece of cardboard, shiny side out. It makes a good reflector that’s not quite as soft in effect as a matte white surface—great for adding sparkly highlights.

4. The farther the light source, the more it falls off— gets dimmer on your subject.

The rule says that light falls off as the square of the distance. That sounds complicated, but isn’t really. If you move a light twice as far from your subject, you end up with only one-quarter of the light on the subject.

In other words, light gets dim fast when you move it away— something to keep in mind if you’re moving your lights or your subject to change the quality of the light.

Also remember that bouncing light—even into a shiny reflector that keeps light directional— adds to the distance it travels.

Tip: If your subject is front lit by window light, keep the person close to the window to make the room’s back wall fall off in darkness. If you want some illumination on the wall, though, move the person back closer to it and away from the window.

5. .Front lighting de-emphasizes texture; lighting from the side, above, or below emphasizes it.

A portraitist may want to keep the light source close to the axis of the lens to suppress skin wrinkles, while a landscapist may want side lighting to emphasize the texture of rocks, sand, and foliage. Generally, the greater the angle at which the light is positioned to the subject, the more texture is revealed.

Tip: For spark in a back lit portrait or silhouette, try compositions that include the light source.

6. Side Light

Side light is light coming from the left or right of the subject. It was used by the masters of painting—Rembrandt used side light in his paintings to give the picture a three dimensional effect. When the light falls on one side of the subject, the other side is in shadow. The shadows are what give the picture a 3D look.

The monk walking past old wooden doors shows how shadow and light can create the contours that make the subject look three-dimensional.

Early mornings and late afternoons are great because the sunlight is more orange; the angle of the light is also more from the side, especially at sunrise and sunset. But also in the hours right after sunrise and the hours just before sunset, the light is not as harsh as in midday.

7. Back Lighting / Shadows create volume!

That’s how photographers describe three dimensionality, the sense of seeing an image as an object in space, not projected on a flat surface.

Again, lighting from the side, above, or below, by casting deeper and longer shadows, creates the sense of volume. Still-life, product, and landscape photographers use angular lighting for this reason.

Back lighting happens when the light source is behind the subject. This means that the light is directly in front of the camera, with the subject in between.

Tip: For spark in a back lit portrait or silhouette, try compositions that include the light source.

In cases of really bright light behind the subject, like in this shot of colorful spools of thread in by a window, the patterns created by the light and shadow make for an interesting picture.

Backlight can be used as highly diffused lighting.

Very few subjects are totally back

lit, that is, in pure silhouette, with no light at all falling from the front. A person with his back to a bright window will have light reflected from an opposite wall falling on him. Someone standing outside with her back to bright sunlight will have light falling on her from the open sky in front of her.

**************************************************************************************

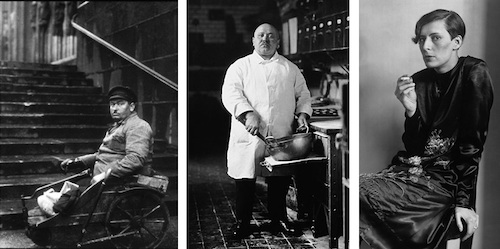

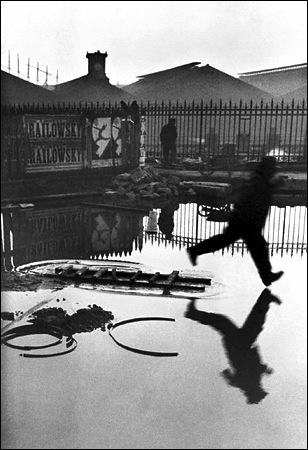

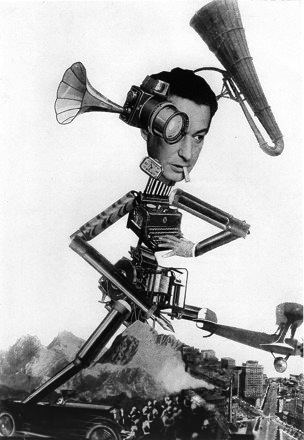

From ten of the following images, select five and identify the origin(s) of the light and specifically how this impacts the message the photographer wishes to convey through the image. Your descriptions will suffice in my identifying the photo.

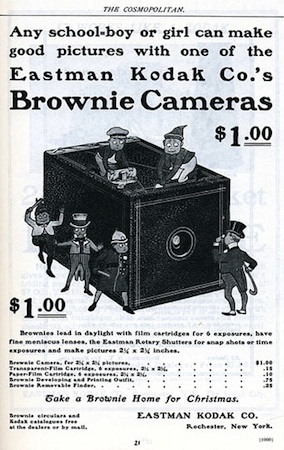

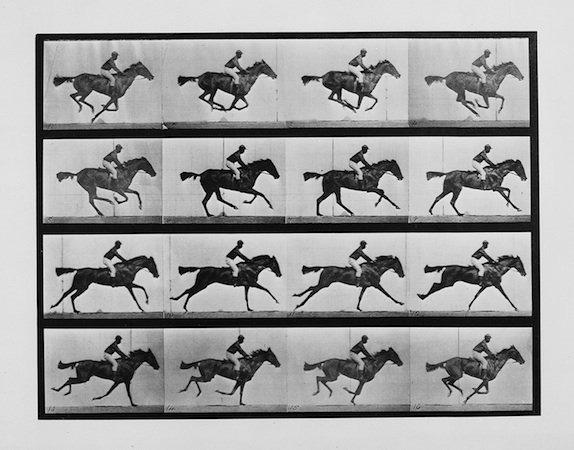

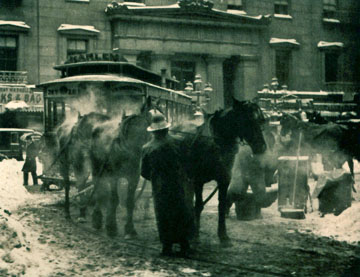

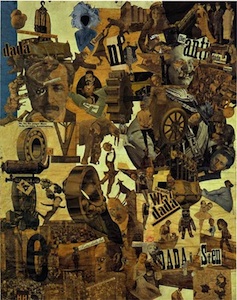

1

2.

3

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.